MADWORKSHOP featured in Dwell on Design Magazine!

It’s a common complaint about architecture school: Students graduate with a portfolio full of ambitious proposals but never really build anything. Martin Architecture and Design Workshop (MADWorkshop) is trying to make that a thing of the past.

“We want to be the catalyst to get student ideas into reality,” says architect David Martin, who cofounded the nonprofit with his wife, Mary. In its first two years, the Santa Monica–based incubator has seen students reimagine everything from public furniture to 3D-printed wearable tech. But their biggest challenge so far has been partnering with the University of Southern California School of Architecture to tackle the homelessness crisis in Los Angeles County, where an estimated 47,000 people are chronically without housing.

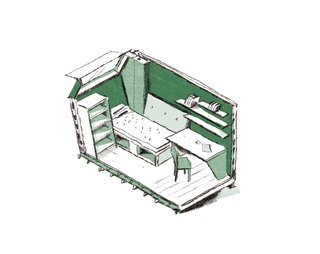

Illustration by Peter Oumanski

“We started by studying homelessness as an architectural typology,” says Sofia Borges, MADWorkshop’s acting director and co-leader of the Homeless Studio program. To understand the problem, 11 fourth-year students embarked last fall on a series of assignments: creating a shopping-cart-sized shelter, crafting a structure from found materials, and designing a prototype modular system that could be used to provide an “emergency stabilization” solution as the city embarks on a $1.2 billion project to build 10,000 permanent apartments for homeless people over the next decade.

“The first exercise developed empathy and the second developed building and construction skills,” says Borges. “The third,” she adds, “was what we really needed to do for the semester,” referring to the modular system the students developed, which they used to design a 30-unit women’s shelter for Hope of the Valley Rescue Mission as a pilot. Along the way, the students navigated the city’s labyrinthine permit process and building codes, which, due to seismic, fire, and hillside concerns, are among the most stringent in the country. “If you can do it in L.A., you can do it anywhere,” explains R. Scott Mitchell, Borges’s partner.

Illustration by Peter Oumanski

Though the semester is over, Hope of the Valley continues to raise money to build the shelter. And the students expect that if the project begins to scale, costs will go down, enabling similar housing solutions to be used around the country. It’s a cause for hope for MADWorkshop, but that doesn’t mean the Martins are planning to stop there. They’re already looking to the incubator’s next challenge: emergency architecture to be deployed in areas affected by disaster.

“Our mission is not to solve social ills, but to say that the design process can be used in a number of ways that can benefit society,” David Martin says. “It could be medicine, architecture, or even some form of fashion. Our thought is, it’s the design process that’s exciting, and if we can be the catalyst to get some of these societal issues under the focus of these creative young people, then that’s a good idea.”